Liturgy and Ritual

The Interwoven nature of Byzantine Imperial and Religious Powers and Influences

The use of religion to legitimize an emperor's authority was common throughout Roman history. The Roman imperial cult deemed the emperor divinely sanctioned with authority, whether as godly intermediaries or as divine in their own right intermediaries or divine in their own right. When Constantine the Great converted to Christianity in 312 C.E. and adopted it as the Empire’s state-sponsored religion, he did not discontinue this practice. Rather, he established the Emperor as the patron protector of Christianity and along with it, the Emperor as the supreme authority in all matters both religious and secular.

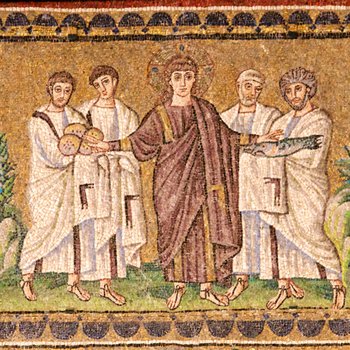

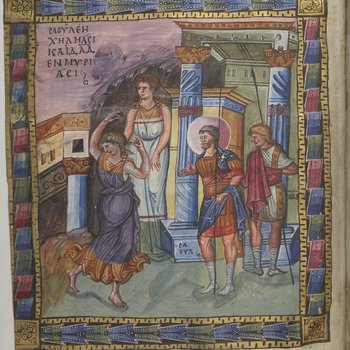

As a consequence, Byzantine liturgical practices were inexorably linked with the exaltation of Imperial powers; a legacy that lasted from 330 C.E. when Constantine moved the Roman capital to Constantinople (considered the beginning of the Byzantine Empire by modern historians), to the empire’s fall in the 15th century. This is evidenced by the countless depictions of Imperial figures that appear in places of worship, on religious monuments, in Christlike scenes, or even in works with Christ himself.

Liturgy and Ritual Objects

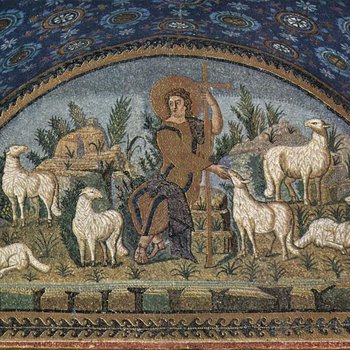

Liturgy, the practice of public worship, is characterized by communal activities and rituals held as sacred. Objects involved in these rituals were often made using precious materials, sometimes with intricate detailing. Some such objects used in the Eucharist: shallow vessels called Patens intended to hold bread representing the body of Christ and goblets to hold wine representing his blood. The scriptures read within these churches, themselves, became works of art in the form of ornate manuscripts. Even the walls of churches were covered in mosaics with scenes from scripture and the life of Christ in order to impress upon viewers the sacred nature of the building and their visit there.

Icons, Relics, and Saints

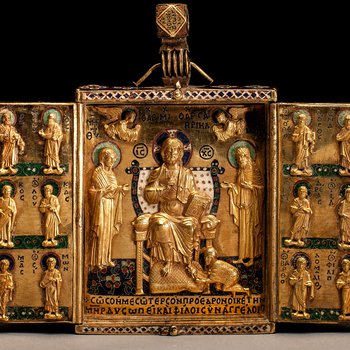

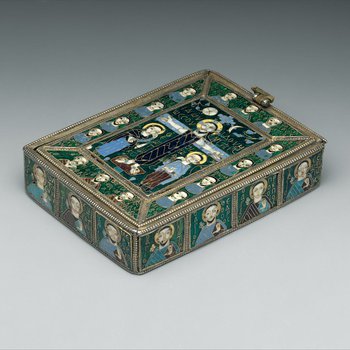

Icons are sacred images that represent Christ, the Virgin, and Saints. They were intended to be used to communicate to the depicted figure through contemplation of the item and prayer. Icons inhabited many spaces both personal and public and could be found in most sizes and materials.

The use of icons also expanded to be used alongside relics: remains of or objects related to a deceased individual to be venerated. These relics held incredible spiritual significance to Christian worshipers, becoming sites of pilgrimage. However, with the rise of icons, so too did a debate on their use: the use of relics and special images of Christ led to Byzantium experiencing a period of iconoclasm. Iconoclasm is the destruction of images and was the result of contention between the church believing icons, relics, and images were worshiped over Christ.

All of these elements, the control of Christianity in the empire; the use of relics and icons; and the period of iconoclasm, influenced the Byzantine empire to become a culture with rich artistic elements and treasured artifacts.