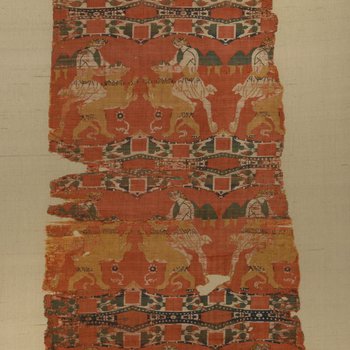

The Byzantine Empire spanned through the 4th to 15th century. Their main textile production was that in linen and wool, which appears in every class structure. Raw silk was imported from China and made into fine fabrics that command high prices throughout the world; Silkworms were smuggled into the Byzantine Empire and overland silk gradually became less important. Constintinople, the capital of the Byzantine Empire, was the first significant silk-weaving center in Europe. Silk was one of the most important commodities in the Byzantine economy and was used by the state as a method of payment and diplomacy. Byzantium dominated silk production in Europe throughout the Early Middle Ages, until the establishment of the Italian silk-weaving industry in the 12th century and the conquest and break-up of the Byzantine Empire in the Fourth Crusade. Byzantine silks are significant for their brilliant colours, use of gold thread, and intricate designs that approach the pictorial complexity of embroidery in loom-woven fabric. After the reign of Justinian I, the manufacture and sale of silk became an imperial monopoly, only processed in imperial factories, and sold to authorized buyers

New types of looms and weaving techniques also played a part in the change of how textiles were produced. Plain-woven or tabby silks had circulated in the Roman world, and patterned damask silks in increasingly complex geometric designs appear from the mid-3rd century. Textiles had patterns influenced from where they were imported from, examples included China, Persia. They had complex mirrored woven patterns that usually depicted Christian subjects.

The majority of textiles that have survived until today come from grave goods. Grave goods mean that these are items that people were buried with. We have knowledge of what people wore during the Byzantine time period due to the grave goods, surviving textual accounts, and depictions in art.